AS a grandmother, Anne Haslam never imagined she would one day have to step into the role of a full-time caregiver.

But four years ago, a distressing call from her grandson’s school changed everything.

Zac, then a pupil at the school, had gone missing during class hours. The school contacted Anne’s daughter, nurse Cybil Joy D’Oliveiro, who immediately took emergency leave and rushed to the school. Anne was informed shortly after.

Zac was eventually found hiding in a toilet, frightened and alone. The incident marked a turning point — not just in Zac’s life, but in Anne’s.

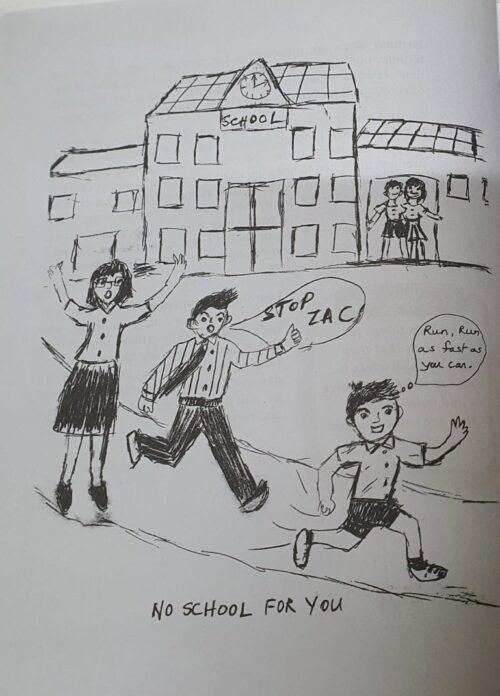

In the three weeks leading up to the incident, the school had lodged near-daily complaints with Cybil and Anne about Zac’s behaviour. He would run up and down staircases, fidget with switches, roll on the classroom floor, sing loudly and distract others, tear notices from the notice board, take another child’s food — and the list went on.

Anne and Cybil had already noticed troubling signs earlier. At one year old, Zac would pull hair, and by the age of three, he had only begun babbling incoherently. He struggled to focus and responded unpredictably. Yet, initial assessments pointed only to sensory perception disorder.

It was only after Zac went missing that the family sought a comprehensive evaluation. Zac was diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Asperger’s Syndrome, which falls under autism spectrum disorder (ASD).

“He couldn’t sit still. He was hyperactive. Before this, we were told it was a sensory perception disorder. But when he disappeared from his class, we knew there was something more,” Anne, a former journalist with the New Straits Times, told Buletin Mutiara in an interview recently.

Anne was 56 when Zac was born in 2015. She committed herself to caring for him full-time — a role she had never anticipated — as Cybil, a single mother and the family’s sole breadwinner, had little choice but to continue working.

Now 66, Anne has spent the past decade navigating therapy appointments, school schedules and emotional setbacks — all while learning, often painfully, how little society understands children on the autism spectrum.

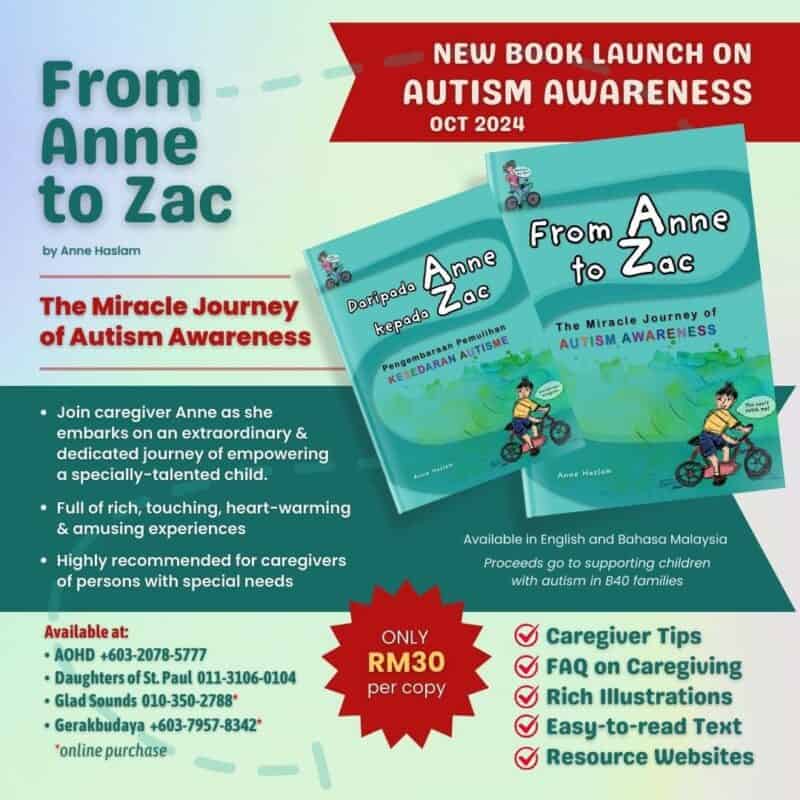

After 10 years of devotion, frustration and hard-earned insight, Anne has written a book, From Anne to Zac, chronicling her journey of struggle, love, learning and transformation as the grandmother of an autistic boy.

Following Zac’s diagnosis, a psychiatrist prescribed medication. However, when its effects wore off, Zac became aggressive. When a more potent drug was suggested, the family decided to discontinue treatment.

They then sought help from a child psychologist in Penang. On one occasion, while driving back to Sungai Petani, Anne had to stop by the roadside to calm Zac, who was experiencing a meltdown — complaining, pulling at her and grumbling, apparently triggered by the afternoon heat.

After six months, they stopped the sessions as Zac showed hardly any improvement. The cost, RM120 per hour, was also a heavy burden. Anne and Cybil eventually took on the role of full-time therapists themselves.

Finding a suitable school was another major challenge. Zac could not attend a mainstream school, while Pendidikan Khas (Special Education) was ruled out as the family feared it might be regressive, with children of different disabilities grouped together.

They finally opted for homeschooling. Zac follows an American-based programme covering history, social studies, creative writing and mathematics, conducted at a daycare centre in Sungai Petani as well as at home.

Bright and intelligent, Zac can speak and write in Bahasa Malaysia, Mandarin and English. While his conversation remains limited, he is hyper-focused on cars and air-conditioners and is highly knowledgeable about their brands.

Asked about the most challenging aspects of raising Zac now that he is 10 and growing physically stronger, Anne pointed to behavioural issues.

“He cannot focus for long, won’t sit still and constantly wants devices and gadgets. Currently, he is a bit addicted to TV, so we try to minimise his screen time.

“If his brain gets overstimulated, he may exhibit behaviours such as stimming or hand-flapping. Sometimes, he becomes aggressive — hitting and pulling hair. We need to help him control himself.

“On top of that, he is becoming more argumentative and wants his own way. We are managing as best as we can,” she said.

Another concern is Zac’s growing awareness of social isolation.

“This is the age when he wants friends, and he feels sad when other children avoid him because of his ‘weird’ behaviour. Social skills are a major challenge for children on the autism spectrum. They don’t know how to interact,” Anne said.

She revealed that she is now working on a second book, Will You Be My Friend?, a picture-based story that remains in its early stages.

Despite the challenges, Zac is naturally friendly and can strike up conversations with ease. When Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow officiated the ‘What’s New in Autism’ forum at SMK Westlands recently, Zac spoke to him as if speaking to a familiar face inside a calming tent. Chow also gave him a warm hug.

To help develop his motor skills, the family enrolled Zac in piano and taekwondo classes. He has also taken up basketball and enjoys playing on the trampoline.

More recently, Cybil has begun training Zac to help make pies — part of her home-based business, Cake and Pie Joy, which she runs via Facebook.

“We want to expose him to pie-making for brain development and to be useful, instead of just watching TV,” Anne said.

“I’m encouraged by a woman who shared that it took her a whole year to teach her autistic child how to hold a spoon and eat. With patience, Cybil and I believe Zac can succeed in making pies.”

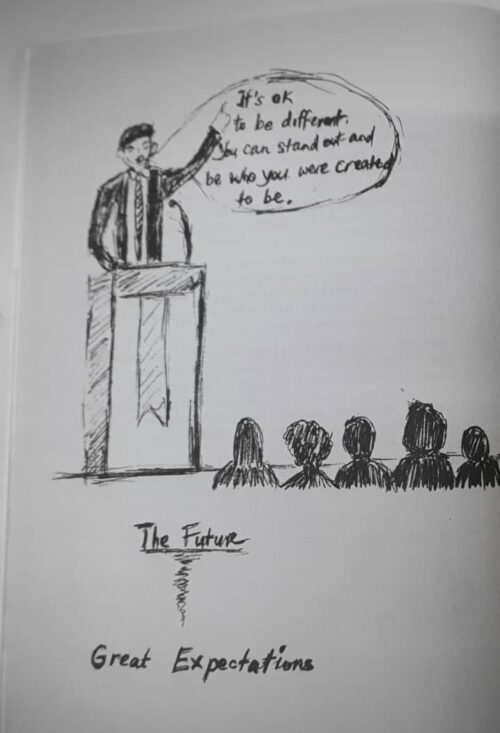

Anne highlighted two prominent autistic individuals — Temple Grandin from the United States, a leading scientist in humane livestock handling, and Malaysian artist Wan Jamila Wan Shaiful Bahri, better known as Artjamila — as examples of what is possible.

As Cybil struggles to make ends meet, she hopes to qualify for the state’s Anak Emas initiative, despite having no marriage certificate. Although Zac was born in Penang and has a birth certificate, she remains ineligible for aid without proof of marriage or divorce — something she hopes could be considered on a case-by-case basis.

There is no doubt that caring for persons with special needs can be physically, mentally and financially exhausting. Some caregivers even fall into depression.

Anne’s book, priced at RM30, is both inspiring and hopeful. It includes her own illustrations, one depicting Zac running while teachers chase after him. Proceeds from the book will go towards an autism centre serving children from lower-income families.

“I want to encourage and motivate other parents and caregivers of children with autism. Sometimes they don’t know what to do. Being part of a community helps. We need to support one another,” Anne said.

Reflecting on their journey, both Anne and Cybil spoke of the joy Zac has brought into their lives.

“For me, Zac is a blessing. Without him, my life would be very lonely. He has helped me grow, change and focus. He is my purpose and gives meaning to my life,” Cybil said.

“After having him, I completed my Bachelor of Nursing and started my pie business. It has given me the chance to include him, so he has something for his future.”

Anne echoed the sentiment.

“Zac has made me a better person — more patient, careful, loving, and kind. It is a very, very difficult journey, and nobody truly understands unless they are in this situation.

“But he has pushed me to rise, to help him, and in doing so, help others too. I cannot imagine my life without him. He has a purpose, and because of him, I wrote a book I would never have written otherwise. I hope it inspires and supports other parents and caregivers on a similar journey.”

Story by K.H. Ong

Pix by Darwina Mohd Daud